Just like the Chinese national flag, Chinese national anthems have great symbolic meanings that have a special place in every Chinese person’s heart. The Chinese national anthem 《义勇军进行曲》Yìyǒngjūn jìnxíngqǔ is translated to “March of the Volunteers” in English. It’s a “fight song” in its essence. Both the tune and the lyrics are uplifting, motivating, and powerful. Keep reading, and you’ll get a chance to hear the Chinese national anthem, study the Chinese lyrics and the English lyrics, see the sheet music, and find out the history and some of the “surprising” facts behind the Chinese national anthem!

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

1. The Tune and the Lyrics

Here is the Chinese anthem 《义勇军进行曲》Yìyǒngjūn jìnxíngqǔ “March of the Volunteers”, the official music video released by the Chinese government:

Below are the lyrics in Chinese and English.

Chinese:

起来(1)!不愿做奴隶的人们!Qǐlái (1) ! Bú yuàn zuò núlì de rénmen!

把我们的血肉,筑成我们新的长城! Bǎ wǒmen de xuèròu, zhù chéng wǒmen xīn de chángchéng!

中华民族 (3) 到了最危险的时候,Zhōnghuá mínzú (3) dàole zuì wēixiǎn de shíhòu,

每个人被迫 (5) 着发出最后的吼声。Měi gè rén bèi pò zhe fāchū zuìhòu de hǒushēng.

起来!起来!起来!Qǐlái! Qǐlái! Qǐlái!

我们万众一心 (4),Wǒmen wànzhòng-yīxīn (4),

冒着 (6) 敌人的炮火,前进 (2) Màozhe (6) dírén de pàohuǒ, qiánjìn (2)

冒着敌人的炮火,前进! Màozhe dírén de pàohuǒ, qiánjìn!

前进!前进!进! Qiánjìn! Qiánjìn! Jìn!

English:

Stand up! Those who refuse to be slaves!

With our flesh and blood, let’s build our newest Great Wall!

The Chinese Nation is at its greatest peril,

Each one is forced to let out one last roar.

Stand up! Stand up! Stand up!

We are billions of one heart,

Braving the enemies’ fire, March on!

Braving the enemies’ fire, March on!

March on! March on! On!

Now let’s be good Chinese learners and study some of the keywords from the Chinese national anthem lyrics.

- 起来 qǐlái “to rise, to get up” [HSK 3 equivalent]

This is the first word in the anthem and is repeated multiple times throughout the song. It means “to get up” or “to rise.” In the national anthem, it’s calling for the people who are 不愿做奴隶 bú yuàn zuò núlì (“not willing to be slaves”) to rise up and fight.

This is a frequently used word in everyday life, used to mean “to get up (from bed).” For example:

你起来了吗?Nǐ qǐlái le ma?

“Are you up yet?”

你几点起来的?Nǐ jǐ diǎn qǐlái de?

“What time did you get up?”

It’s also commonly used as a verb complement. It’s attached to the end of a verb, describing an action that has the “upward” motion or “starting to get [verb].” Let look at these two examples:

你坐着看不见,站起来吧。Nǐ zuòzhe kàn bù jiàn, jiù zhàn qǐlái ba.

“You won’t be able to see when sitting down, you’d better stand up.”

天晴了,我的心情也好起来了。Tiān qíng le, wǒ de xīnqíng yě hǎo qǐlái le.

“It’s getting sunny. My mood is also getting better.”

- 前进 qiánjìn “march on, move forward” [HSK 6 equivalent]

This word also appears multiple times in the lyrics. 前 qián means “front, forward,” and 进 jìn means “to enter, to advance.” This is a formal word that’s often used as a military command, asking the troop to “move forward” or “march on.”

This word is not used as commonly in everyday conversations but in formal reports and literature. Here’s an example:

我们在前进的道路上不断成长。Wǒmen zài qiánjìn de dàolù shàng bùduàn chéngzhǎng.

“We continue to grow along the way (moving forward). “

他突然没有了前进的动力。Tā túrán méiyǒu le qiánjìn de dònglì.

“He suddenly lost the momentum to keep going.”

- 中华民族 Zhōnghuá Mínzú “Chinese people/nation” [HSK 4]

You may have heard this word on the CCTV (Chinese Central Television)’s Spring Festival Gala. 中华 Zhōnghuá is a poetically patriotic way to refer to China, with a focus on the people. For example, 华人 huárén is used to refer to people of Chinese origin, especially those who live overseas. 中华 Zhōnghuá often goes with 民族 mínzú, which means “ethnic group.”

尊老爱幼是中华民族的传统美德。 Zūn lǎo ài yòu shì Zhōnghuá Mínzú de chuántǒng měidé.

“Respecting the old and loving the young is a traditional virtue of the Chinese people.”

中华民族有着很长的历史。Zhōnghuá Mínzú yǒuzhe hěn cháng de lìshǐ.

“The Chinese nation boasts a long history.”

- 万众一心 wànzhòng-yìxīn [HSK 6 equivalent]

This four-character idiom is often used to boost morale and promote patriotism. 万众 wànzhòng literally means “ten thousand people” and figuratively “millions of people.” 一心 yìxīn means “one heart.” Together 万众一心 wànzhòng-yìxīn is used to describe all the people united with a common goal or belief.

我们万众一心,齐心协力,共度难关。Wǒmen wànzhòng-yìxīn, qíxīn-xiélì, gòngdù nánguān.

“We are all united, working together to get through this difficult time.”

万众一心是通向胜利的第一步。Wànzhòng-yīxīn shì tōng xiàng shènglì de dì yī bù.

“Unity is the first step to victory.”

- 被迫 bèi pò “be forced” [HSK 5 equivalent]

The word starts with 被 bèi, indicating a passive voice. 迫 pò means “to force, to compel.” In the lyrics, the Chinese people are forced to 发出最后的吼声 fāchū zuìhòu de hǒushēng “let out one last roar.”

In everyday situations, it can be used in sentences like:

由于天气原因,比赛被迫中止。Yóuyú tiānqì yuányīn, bǐsài bèi pò zhōngzhǐ.

“Due to inclement weather, the game was put to a stop.”

他被迫上交了自己的手机。Tā bèi pò shàng jiāo le zìjǐ de shǒujī.

“He was forced to hand over his cell phone.”

- 冒着 mào zhe “to brave” “to face dangers” [HSK 4 equivalent]

冒着 mào zhe is a verb that means “to brave” or “to face dangers” in this context. In the lyrics, it’s asking the Chinese people to brave the enemies’ bombs and bullets and march on – 冒着敌人的炮火,前进! Mào zhe dírén de pàohuǒ, qiánjìn!

This verb in everyday life is often paired with 雨 “rain.” Such as:

她是冒着雨来的。Tā shì mào zhe yǔ lái de.

“She came in the rain” (showing her determination to come here despite the rain)

Besides the above Chinese words, if you’re also interested in playing this tune, copyrighted sheet music can be found on this Chinese government website.

2. The Occasions

As the solemn symbols of the country, the Chinese national anthem《义勇军进行曲》Yìyǒngjūn jìnxíngqǔ and the Chinese flag 五星红旗 Wǔxīng-Hóngqí “the five-star red flag” often go together in formal ceremonies. In Chinese, this procedure is called 升国旗,奏国歌 Shēng guóqí, zòu guógē. “Raise the national flag, and play the national anthem.” People are encouraged to sing along with the music.

Globally, the national anthem is played with the flag being raised at international sporting events such as the Olympics 奥运会Àoyùnhuì.

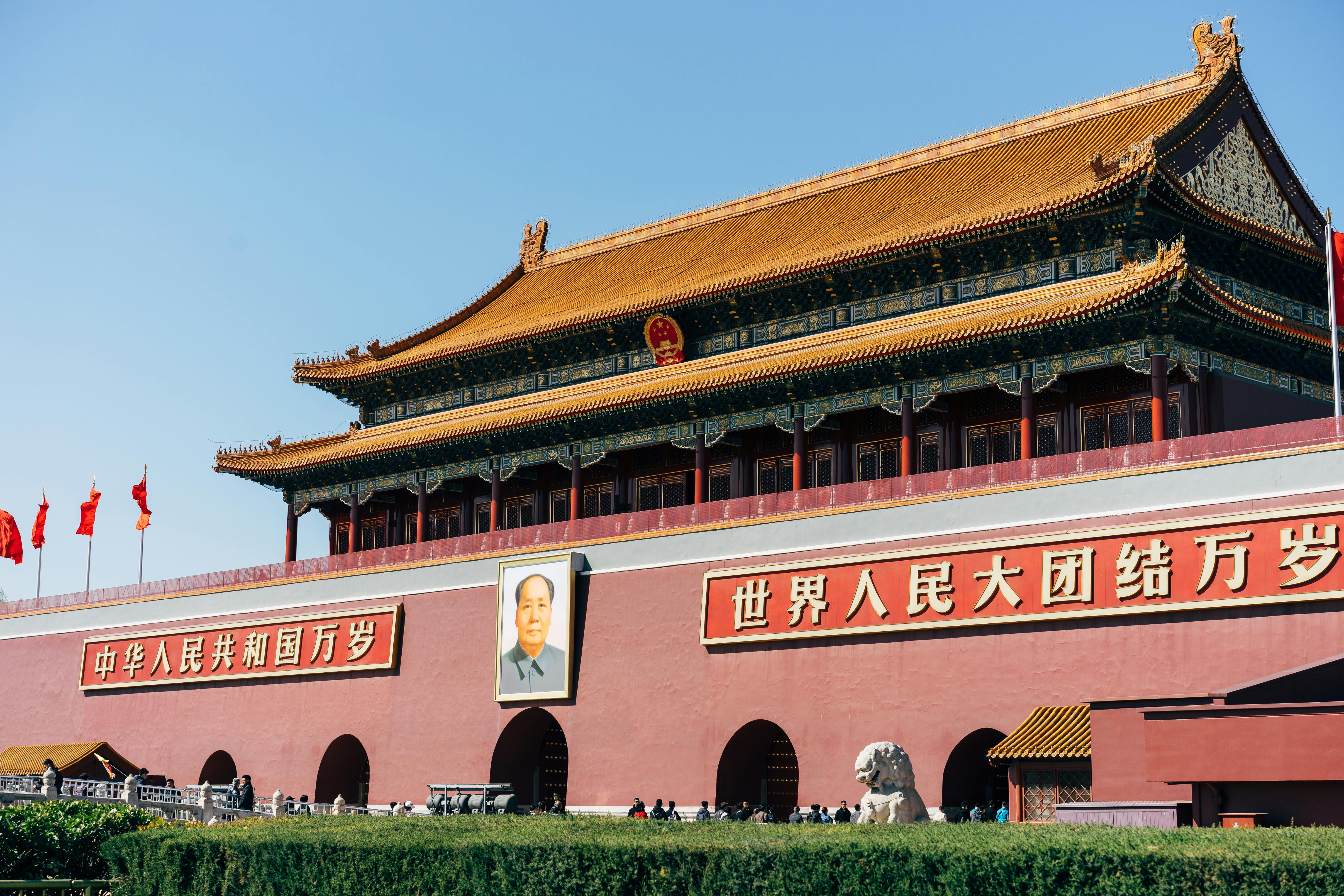

Nationally, the national anthem is played when the flag is being raised at the Beijing Tiananmen Square daily precisely at sunrise, performed by the PLA (People’s Liberation of Army). You can find the daily flag-raising ceremony timetable on this website.

At higher administrative levels in China, the anthem is played at political occasions, such as on the 国庆节 Guóqìng jié “National Day” celebration, 人大会议 rén dà huìyì National People’s Congress meeting, etc.

In primary and secondary public schools and some government organizations, there is a weekly 升旗仪式 shēng qí yíshì “flag-raising ceremony” where the national anthem is played while the flag is being raised on the pole while the students or employees sign the national anthem.

3. The Facts

- The Chinese national anthem was initially created for a movie.

In 1934, 田汉 Tián Hàn “Tian Han” wrote a poem that was intended for part of a script for the movie 风云儿女 Fēngyún érnǚ “Children of the Troubled Times,” a movie about a Chinese intellectual fighting the Japanese occupation of the northeast part of China.

In 1935, 聂耳 Niè Ěr “Nie Er” composed music for the words, which was eventually recorded as a song for the movie.

In 1949, the song “March of the Volunteers” was used as the Chinese national anthem for the first time at the World Peace Council, and was finally chosen to be the official anthem by the Communist party a few months before the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949.

- “The March of Volunteers” was performed in Chinese by an American artist.

In 1940, Paul Robeson, a college-educated polyglot and artist, started performing “March of Volunteers” in Chinese at a large concert in New York City. Together with the lyricist Tian Han, they translated the Chinese into English, and recorded the song as 起来 Qǐlái “Chee Lai,” which was performed multiple times at major international events.

- The Chinese national anthem was temporarily replaced during the Cultural Revolution.

In 1966, the song 东方红 Dōngfāng hóng “The East is Red” replaced “March of Volunteers” as the chairman 毛泽东 Máozédōng Mao Zedong‘s effort to promote his image and idealizes himself. The song was later adapted to a movie with the same title, “The East is Red.” It wasn’t until 1970 that “March of Volunteers” became the national anthem again.

- The law protects the Chinese national anthem and flag.

In 2017, the Chinese national anthem law was passed, stating on what occasions the national anthem should be played, how the official recordings provided by the government (see linked site above) are the only ones allowed to be played, and what the consequences of insulting the national anthem, such as altering the lyrics or singing it in a distorted way, were.

The law remains controversial, especially in Hong Kong. You can read more about it here.

4. The Final Words

It’s amazing how much you can learn about a language and its culture from a national anthem, isn’t it? Next time you hear the Chinese national anthem, try translating the lyrics and see if you can remember the words discussed in this article!

Don’t forget whenever you need a little extra help, ChineseClass101.com is always here! Explore the abundant vocabulary lists, practice with audio recordings and speak with more confidence. It’s never too late to join!

If you’d like to further boost your Chinese skills and learn with specific goals, you can always upgrade to Premium PLUS subscription and get 1-on-1 coaching from your own private teacher, who will customize a Chinese learning pathway just for you!

Ask your teacher about personalized exercises, assignments, and audio samples; they would be more than happy to find the right materials for you. On top of that, feedback and necessary corrections will always be ready for you within 2 business days. Find your private teacher now on ChineseClass101.com!